Skywatching FAQ

Frequently asked questions about skywatching, answered by NASA.

General Questions

- What is skywatching?

Skywatching refers to observing the ever-changing variety of sights in the sky, at night in particular, but also in the day. Skywatching can be as casual as enjoying a couple of minutes of stargazing, and as serious as using a telescope to take images of deep sky objects. When you notice the changing position and phases of the Moon over a few days, or you search for Jupiter or Venus in the twilight sky, or you notice a constellation like Orion is visible for the first time in a few months, you're skywatching. At its heart, skywatching is an activity anyone can engage in to feel more connected to the larger world beyond planet Earth. - What tools do I need to start skywatching?

You don't need any special equipment to get started skywatching. Online resources like this page are a great place to learn about what you can see. An app on your smartphone or computer can be a great help to discover what sights are visible tonight, and where to find them in the sky once you're outside under the stars. If you have access to binoculars or a telescope, they will extend your vision and enhance the experience – but they are by no means necessary to get started. - How do I find a good location for skywatching or stargazing?

The number one priority when seeking an excellent location for skywatching is to get away from bright city lights. Scattered light from urban areas creates light pollution that washes out the fainter stars and the Milky Way. Wide open areas without lots of tall trees or mountains nearby make for good viewing spots, since you can see more of the sky. Examples include places like a large field, a wide valley, and the shore of a lake or the ocean. Any location you select should be a place where you can feel safe at night.

> More about finding a good skywatching location - What can I see in the night sky?

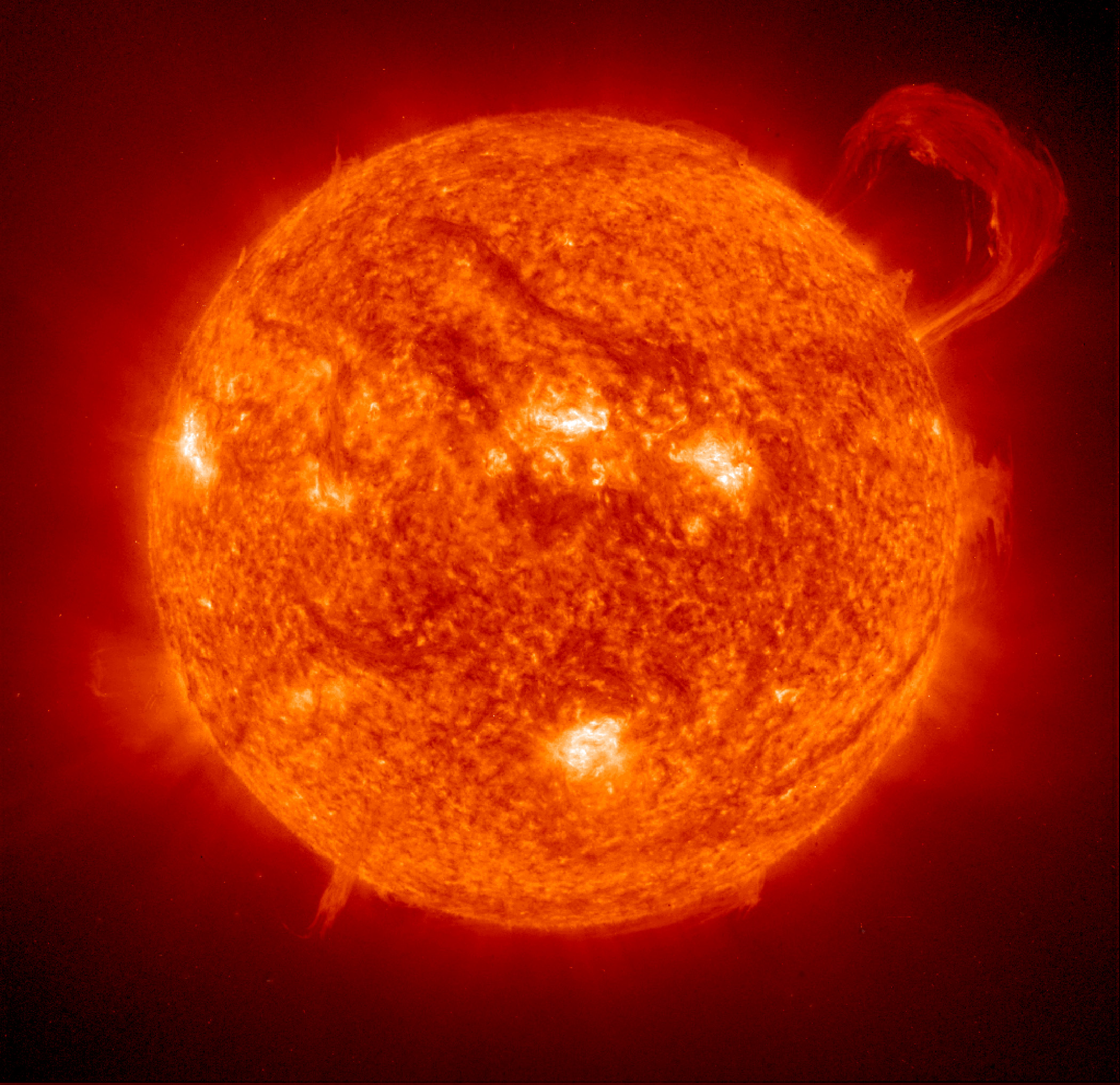

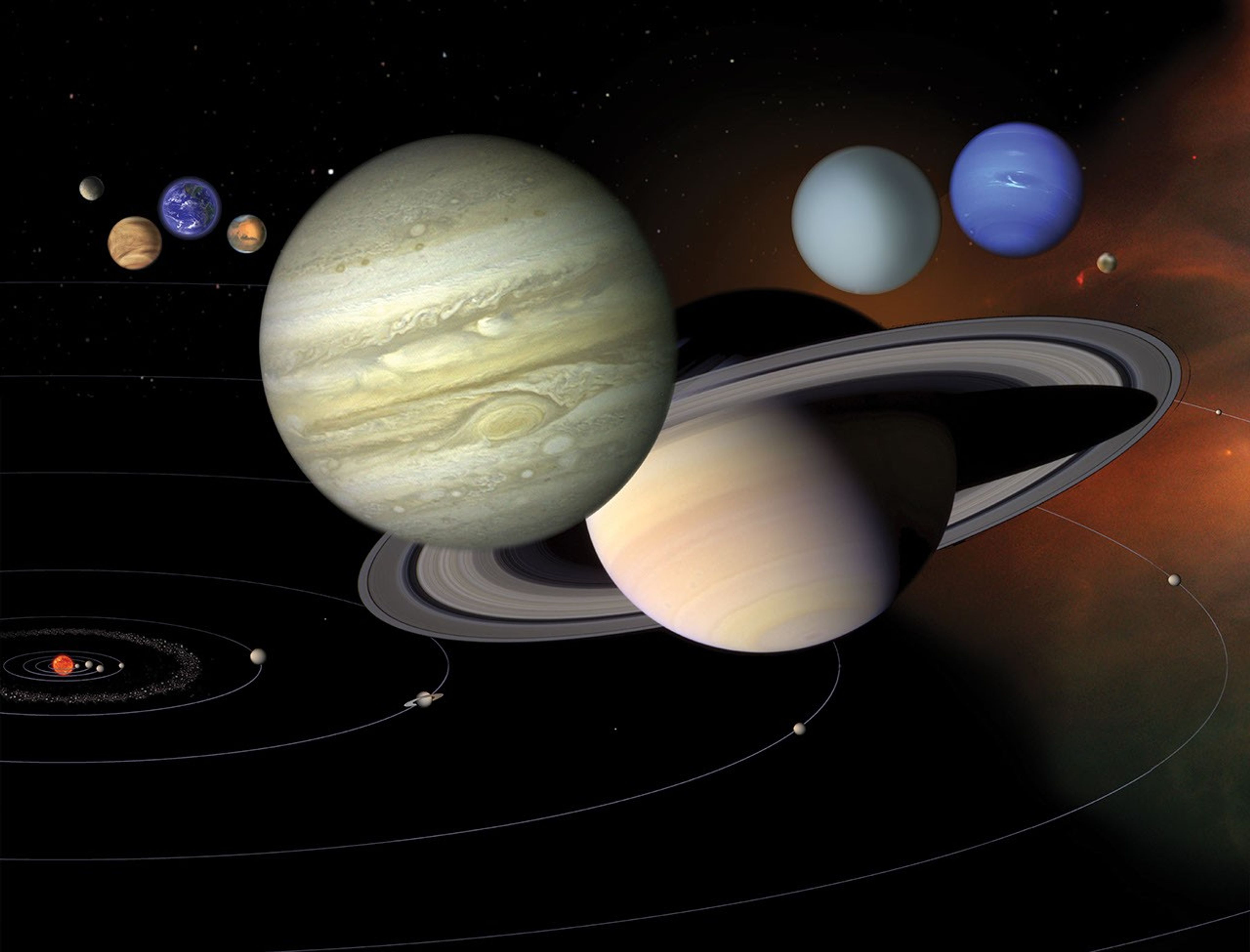

The whole universe is accessible to skywatchers. Your own eyes will show you stars, a handful of bright planets, the Moon, comets and meteors (shooting stars), to name a few sights. Binoculars or a small telescope enable you to see finer details than your eyes can detect, making visible things like the large moons of Jupiter and the rings of Saturn, as well as star clusters and double stars. A larger telescope enables you to see fainter objects, like nebulas and other galaxies. - How does light pollution affect skywatching?

Light pollution is stray light from parking lots, sport complexes, street lights, and other human activity, scattered into the night sky. It's a combined effect of scattered light from these things that manifests as a glow in the night sky that makes it difficult to observe fainter stars and the Milky Way. The larger and more developed a city is, the more light pollution it tends to produce. The effect decreases the farther away you travel from a city. Heading out to less developed areas, away from town, will enable you to see more stars.

> More about how light pollution impacts locations for stargazing - Can I see ____ from my location on Earth? How do I know if objects and events described here are visible where I live?

Most skywatching phenomena featured on these webpages and in our What's Up videos are visible for observers across the mid-latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere (that is, from about 25° to 50° north latitude). Plenty of these highlights are also visible from other locations farther north and south.

If an object like a star or planet appears high overhead for the U.S. mainland, then it will also appear high overhead across much of Europe, the Mediterranean and Middle East, and Eastern Asia. These regions share the same range of latitudes, so their view of the night sky is similar.

We recommend using skywatching apps for mobile devices and computers for determining if something can be seen from your location, and when to look for it. They enable you to enter your location on Earth and see the sky as it will look on a particular date and time. - How big is a "degree" when describing how close objects appear in the sky?

A degree is about the with of your little finger held at arm's length. Most of us are familiar with the idea that there are 360 degrees in a circle, and that making a 180-degree turn is to face the opposite direction. If you imagine the sky as a sphere with the stars fixed onto it and pick any point, and draw a circle all the way around the sky until you return to that point, you will have rotated through 360 degrees.

To approximate 5 degrees, hold up your three middle fingers on one hand. For 10 degrees, hold up a fist.

Stars and Constellations

- What is is the difference between a constellation and an asterism?

The 88 star patterns officially known as constellations are regions the sky is divided into that help astronomers identify where objects are located on the sky. Asterisms are familiar shapes and patterns of stars that are not constellations, and that often include stars shared by multiple constellations.

Whereas constellations tend to have names and stories that come from mythology or the animal kingdom, asterisms often have less formal, more whimsical names, including the Teapot and the Big Dipper (aka the Plough). Some asterisms are simply named for the shapes they represent on the sky, such as the Summer Triangle and the Winter Hexagon (aka the Winter Circle).

> More about asterisms - What is the brightest star?

The brightest star in our skies – that is, the star that appears brightest to us on Earth – is Sirius. In terms of absolute brightness (that is, if you place the Sun and Sirius at the same distance) it's around 25 times brighter than the Sun. Fortunately, Sirius is located about 9 light years away. Sirius is a very bright star, to be sure, but it's only the brightest one in our sky because it's relatively close by in cosmic terms.

It's not known what the absolute brightest star in the Universe is, but one of the brightest known stars is called R136a1. It is about 6 million times brighter than the Sun, and it's located about 160,000 light years away. - What is the North Star? How do I find the North Star?

The North Star, Polaris, is a helpful guide in the night sky for those in the Northern Hemisphere. It would appear directly overhead if you stood at the North Pole, but farther south, it indicates the direction of north. It always stays in essentially the same spot in the sky, and therefore it's a reliable way to determine which way is north at night.

Locating Polaris is easy on any clear night. Just find the Big Dipper. The two stars on the end of the Dipper's "cup" point the way to Polaris, which is the tip of the handle of the Little Dipper, or the tail of the little bear in the constellation Ursa Minor.

> More about the North Star

The Moon and Planets

- Why does the Moon have phases each month?

Earth's Moon is continuously illuminated on one side by the Sun, so if you were to fly around the Moon in space at any given time of the month, you'd always observe that one half is the sunlit side and the other half is the dark side. But over the course of each month, the Moon orbits around Earth, and our view of the Moon changes. We see it from a slightly different vantage point each night. And even though the total amount of the Moon's surface illuminated by the Sun doesn't change, we see a different view of that half-lit, half-dark object each night. That changing view is what we perceive as the Moon's phases.

You might ask why we always see the same side of the Moon if it's actually rotating, which is a great question. The reason for that is because the Moon rotates at the same rate as it orbits our planet – that is, both take about a month. Through an effect related to gravity and the forces that cause ocean tides, the Moon has become locked in this orientation, so that it always points the same side toward Earth. Some of the other moons of the solar system are also "tidally locked" to their planets like this as well. - Why does the Moon rise and set at different times each day?

The Moon rises, on average, about 50 minutes later each day during its month-long cycle. The reason is that the Moon is moving in its orbit around Earth. It takes about 27.5 days to make each orbit, and Earth spins beneath the Moon once every 24 hour day. Each day when Earth completes a full rotation, the Moon has moved a little bit in its orbit, so it doesn't rotate into view above the horizon until Earth rotates a little bit further. Looking at the Moon in the night sky, we see it move slightly (about 12-13 degrees) each night, toward the East, with respect to the fixed stars and slower moving planets. - When is the best time to see Mars, Saturn, Jupiter, Venus, Mercury?

There are five planets you can easily see with the unaided eye. The best time to see them depends on whether their orbit is closer to the Sun than Earth's or farther away.

Mercury and Venus are closer to the Sun, and they never appear to move too far away on the sky from our local star. Thus these two planets will always be seen near sunrise and sunset. Mercury is closest to the Sun, so it always rises or sets soon before or after the Sun. Venus orbits farther out than Mercury, so it lingers up to a couple of hours before or after the Sun comes and goes.

The highest point Mercury and Venus reach in the sky, which makes it easiest to observe them, is called their greatest elongation – it's a fancy way of saying the farthest away they appear get from the Sun. Each planet appears to move back and forth along a line to the left and right of the Sun from our vantage point. At greatest elongation, they reach the end of that line and start to head the other way. (Of course, what's really happening is they're orbiting the Sun, but we're seeing that happen from the side, so they appear to move back and forth over the months.)

Mars, Jupiter and Saturn orbit the Sun farther out than Earth does. The best time to observe them is around the time when they're at what's called opposition. This is the time each year when each planet lies directly opposite of the Sun from Earth – that is, along a line from the Sun to Earth to the planet. Near opposition, the planet is visible all night and appears high overhead around midnight. - Why do we call the Earth's moon "The Moon," when there are lots of other moons orbiting other planets?

Until just a few hundred years ago, we didn't know other planets had moons of their own. Our Moon was the only one we knew of. It wasn't until astronomers began to study the planets with telescopes that they observed there were objects that appeared to be orbiting them. Galileo was the first to do so, but he referred to the moons of Jupiter as both "stars" and "planets." (He wasn't quite sure what the objects were that he had discovered.) The astronomer Kepler called them satellites, which is a term we still use today (calling moons "natural satellites"). It was the astronomer Huygens, discoverer of Saturn's moon Titan, who first used the term "moons" to characterize these natural satellites as being something akin to Earth's Moon. (Science fiction stories sometimes imagine a future time when Earth's Moon is simply called Luna, which is the Latin word for moon.) - What is the brightest planet?

Venus is the brightest of the planets seen from Earth. After the Sun and the Moon, Venus is the next brightest object. Jupiter, at its brightest, is nearly as bright as Venus is at its faintest. Jupiter is generally the brightest of the remaining planets, but it's sometimes even fainter than Mars. The brightness of the planets varies as both they and Earth orbit the Sun, moving closer and farther away from each other. This is true for Venus as well, but it has several factors in its favor: it's closer to the Sun than all but Mercury, its orbit is closer to Earth's, and it's as big as Earth (that is, it's larger than Mercury).

Skywatching Resources

- Do you offer skywatching resources in Spanish?

Yes, our monthly What's Up videos are closed captioned in Spanish via the NASA-JPL YouTube Channel. You can also find great skywatching resources for kids in Spanish at NASA Space Place: https://spaceplace.nasa.gov/sp/ - Where can I find more NASA resources about skywatching?

NASA provides a variety of skywatching resources to help you make a personal connection with the amazing place we study and explore. These include:

> "What's Up" monthly skywatching highlights video

> Night Sky Network (astronomy clubs & events)

> Eclipses (NASA's hub for solar and lunar eclipse info)

> Watch the Skies blog (meteors & meteor showers)

> Spot the Station (see the International Space Station pass overhead) - How can I involve my children in skywatching?

Parents can prepare to involve their children in skywatching by learning some of the basics, like the phases of the Moon, the names of a few easy to recognize constellations, and knowing how to identify bright stars and planets using a favorite astronomy app. Staying up to date with the month's skywatching highlights, with resources like NASA's What's Up video series, makes it easy to know what there is to observe, and provides some fun facts to share when out under the stars. If you don't have easy access to a safe place for the family to stargaze, most local astronomy clubs host public viewing nights, where children can enjoy telescope views of the sky's wonders.

You can also look for astronomy clubs and events in your areas with NASA's Night Sky Network.

NASA's Space Place also offers skywatching resources for kids, including these articles:

> What are Constellations?

> What is a Solar Eclipse?

> What is a Meteor Shower? - Where do you find the photos and videos featured in the What's Up videos?

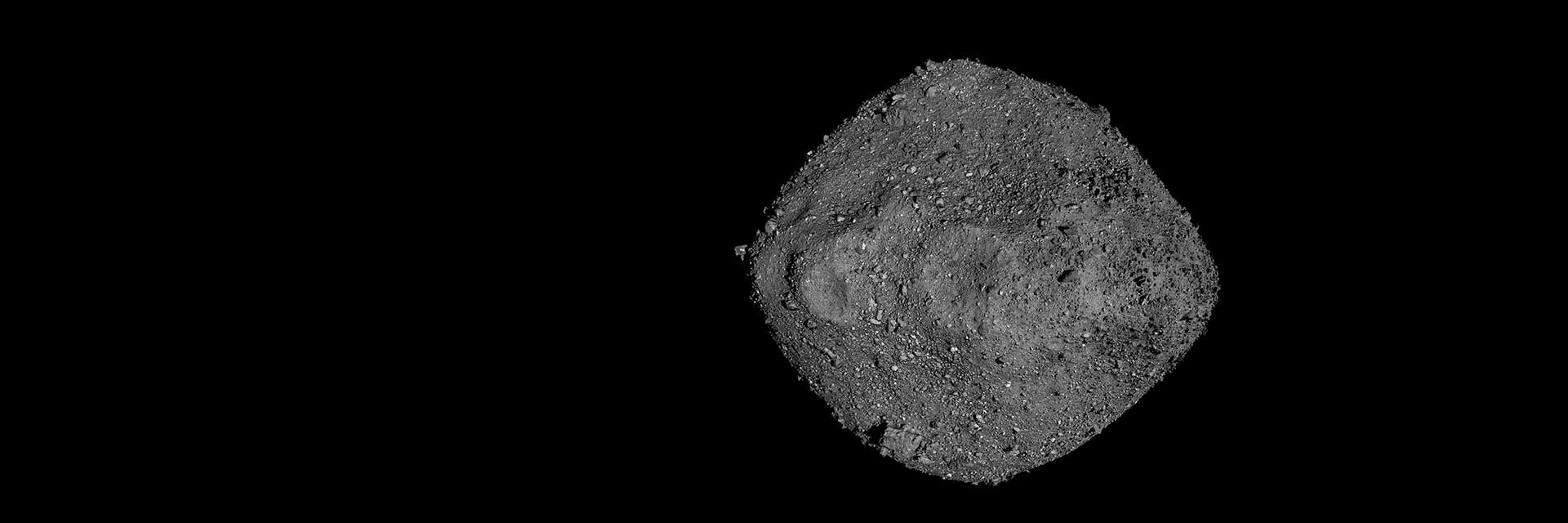

The photos and video clips featured in What's Up come from a variety of sources. Many are sourced from online photo-sharing communities under Creative Commons licenses. For those that are copyrighted, we request permission directly from the content creators. Some media are night sky images taken by members of our team at NASA as part of their own astrophotography hobbies. We use a variety of other sources as well, such as Wikimedia Commons and the National Park Service.

If you'd like to use photos from What's Up or this NASA website, take note of the image credit. Creative Commons licenses are listed at the end of each What's Up video. If a Creative Commons license is not indicated, it's best to assume the image is copyrighted and you would need to contact the owner of that media to ask for permission. For questions, please contact us. - Why do you mostly focus on skywatching in the Northern Hemisphere? Why don't you provide more info for the Southern Hemisphere?

Being the U.S. space agency, our primary audience is the American public, whose tax dollars fund NASA's work. Thus we tend to focus on skywatching topics that can be observed from there. However, NASA has a global reach, and we do try to note relevant facts for skywatchers in the Southern Hemisphere when it's practical to do so. In our videos, sometimes the choice not to include Southern Hemisphere tips is just a matter of keeping them close to our standard runtime. We tend to avoid featuring events that can only be seen outside the U.S. – for example, an eclipse only visible in South America and the South Pacific.

Keep Exploring